OPINION - How I came to understand Alija Izetbegović better over time

Long before Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Alija Izetbegović was offered a choice between the destruction of his people and his country by a cynical class of international diplomats and negotiators

The author is the director of the Srebrenica Memorial Center. A part-time lecturer at the International Relations Department of the International University of Sarajevo (IUS), Dr. Suljagić is also the author of two books: “Ethnic Cleansing: Politics, Policy, Violence - Serb Ethnic Cleansing Campaign in former Yugoslavia” and “Postcards from the Grave”

ISTANBUL

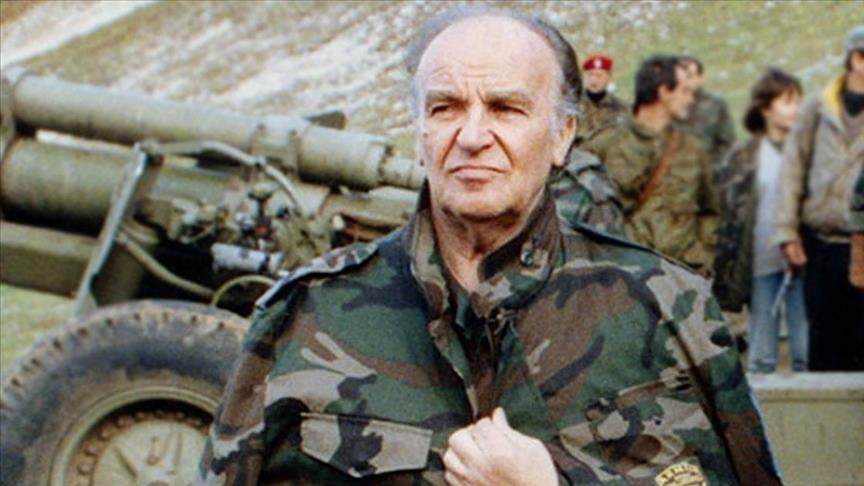

I met the man only once. He was coming down the stairs of Dom Armije in Sarajevo city center. I was a student spending my summer break volunteering at a genocide conference. As we passed, he nodded, and I nodded back and greeted him as politely as I could. In fact, I was angry with him.

- Izetbegović was too human in a profession reigned by inhumanity

I have always had a complicated relationship with Alija Izetbegović, the first president of independent Bosnia and Herzegovina. After I came out of Srebrenica, I was burning with questions about the kind of peace he signed and the kind of state that he signed off on.

If anything, I was an etátist, and I believed that the type of state we should have come away with from the Dayton Peace Agreement should have been more robust. I found Izetbegović soft, all too human in a profession reigned by inhumanity, out of place in an environment where duplicitous diplomats wined and dined with war criminals.

A few years later, I interviewed the former US Ambassador to Croatia, Peter Galbraith, for Dani, my newspaper. It was eye-opening in many ways. In a moment of unique candor for a diplomat, Galbraith explained US foreign policy considerations when pressuring the Croatian and Bosnian governments to stop their joint offensive short of entering the Bosnian Serb capital of Banja Luka in September 1995.

- The environment in which he had to operate was a tough one

The main concern in conducting the negotiations and concluding peace in Dayton was to ensure the stability of the regime of Serbia's Slobodan Milošević. The US was worried that there could be political instability in Serbia as a "consequences of a refugee wave of 400.000 people who would move (…) and the catastrophe it would cause".

It dawned on me that three months after the fall of Srebrenica, despite all the evidence that the US government must have had about it --substantial evidence was thankfully submitted by the US authorities to the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), as well as significant investigative aid-- it was still primarily concerned with preserving the Milošević's regime. I found the US's response to be extremely cynical. It also made me start thinking about the international context and environment in which Alija Izetbegović had to operate.

- They could never get past the fact that he was a Muslim

Today I realize that long before Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Alija Izetbegović was offered a choice between the destruction of his people and the carving up of his country by a cynical class of international diplomats and negotiators. For all the kind words the Western diplomatic and political establishment heaped upon him after his passing, the truth of the matter is that during the nineties, they refused him in any other but religious terms. Yes, he was a Muslim, and they could never get past that fact. When negotiating with him, genocide against his people was considered a legitimate diplomatic tool.

I never spoke with Izetbegović, but in the later years, as the only Bosnian correspondent from the ICTY, I had an opportunity to read what he said when the outside world did not listen, in meetings with other heads of state, prime ministers, ministers, and many so-called "special envoys".

- He was determined, standing up for his country

To be honest, I was looking for evidence of the beliefs I already held about him, but I found something completely different. I found a determined man capable of standing up for his country, the citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and his own values, even when at his weakest. It would have been impossible to gain independence for Bosnia and Herzegovina under any other circumstances except those from summer 1990 to spring 1992.

It was a rare moment in history internationally but equally significant regionally. Alija Izetbegović recognized it for what it was and acted upon it. Were it not for his ability to recognize it and to successfully play Slobodan Milošević of Serbia and Franjo Tuđman of Croatia against one another, Bosnia and Herzegovina would have likely ended up as a Serbian province or, at best, would have been divided between Serbia and Croatia. Both Milošević and Tuđman quickly regretted their decisions in the period leading up to Bosnian independence. They tried to "rectify" it, but it was already too late for their plans, by the late summer of 1992, the Bosnian people were standing in their way.

- He took decisions others wouldn't have taken

Izetbegović made crucial decisions in that period that I doubt some other Bosnian politicians would have made at that time. He was not going to leave Bosnia alone and stuck with Serbia in some sort of Greater Serbia, but he also knew he had few allies to pursue independence elsewhere. He was a man formed by the preceding two hundred years of Muslim withdrawal from Europe --like my grandfathers' generation-- and sought initially, like many other Bosnian and Muslim leaders, to settle with Europe on Europe's terms. Whether he planned it or not, he ended up the first Bosnian and Muslim at the table and ensured that the peace settlement was also on our terms.

Maybe I have grown old and mellowed, but I don't think we still understand how difficult it was to gain Bosnian independence and what it took from every one of us. We can still say many things about Alija Izetbegović, but we can't say that he wasn't in it with all of us or that it wasn't his struggle. To deny that to Alija Izetbegović is to deny him being Bosnian and Muslim. He was proudly both.

* Opinions expressed in this article are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Anadolu Agency.