How does social distancing affect our brains?

Scientists thrilled by discovery that working of hormone in zebrafish shows how having others around affects body chemistry

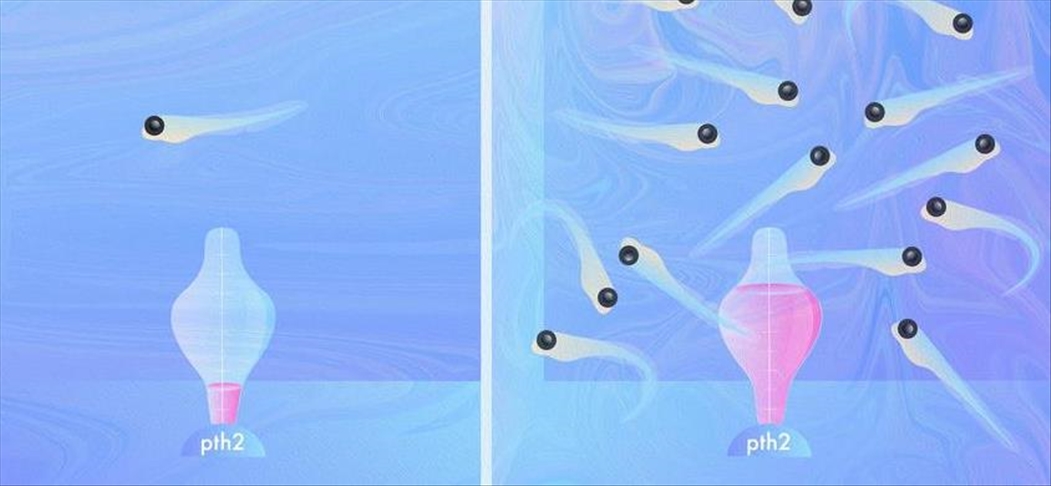

Scientists thrilled by discovery that working of hormone (the neuropeptide Pth2) in zebrafish brain shows how having others around affects body chemistry. Copyright: Max Planck Institute for Brain Research/J.Kuhl

Scientists thrilled by discovery that working of hormone (the neuropeptide Pth2) in zebrafish brain shows how having others around affects body chemistry. Copyright: Max Planck Institute for Brain Research/J.Kuhl

ANKARA

New research is shedding light on how a social environment can impact our brains, showing a surprising role for a relatively unexplored hormone that runs as a "thermometer" for the presence of others in the immediate environment.

According to Robert Sapolsky, one of the world's leading neuroscientists, hormones, social conditions, genes, your childhood, and the culture you grew up in are the key factors that shape the structure of our brain.

And what's more, he argues, the interaction of all of these factors can lead to permanent changes in human behavior.

For example, the coronavirus pandemic, arguably the biggest public health crisis the world ever seen, has changed the very fabric of the way we live.

As social animals, we have had to fight our very nature to practice the necessary but inherently awkward measures of social isolation.

Social scientists have warned of the pandemic's psychological fallout, saying that extreme forms of social distancing may deteriorate or trigger mental problems.

Your brain on social distancing

More recently, a study by the German-based Max Planck Institute for Brain Research tackled the neurobiological process of social distancing, trying to determine how self-isolation may be affecting our brains.

To investigate whether neuronal genes (which affect proteins in the brain) react to dramatic alterations in the social environment, the research team raised zebrafish either alone or with others of their kind.

The scientists found that there is a brain molecule which serves as a kind of "thermometer" for the presence of others in the fish's environment.

When zebrafish sense the existence of others through water movements, this molecule is activated, which turns on a particular brain hormone.

Hormone's surprising role

"Our data indicate a surprising role for a relatively unexplored neuropeptide, Pth2 – it tracks and responds to the population density of an animal's social environment," the institute quoted neurobiologist Erin Schuman, head of the research team, as saying.

Saying that the presence of others can have dramatic consequences on an animal's access to resources and ultimate survival, she said it is therefore likely that this neuro-hormone will regulate social brain and behavioral networks.

"We found a consistent change in expression for a handful of genes in fish that were raised in social isolation. One of them was parathyroid hormone 2 [Pth2], coding for a relatively unknown peptide in the brain," said Lukas Anneser, a member of the team.

"Curiously, Pth2 expression tracked not just the presence of others, but also their density," he added – in other words, how many others there were swimming around.

Intriguingly, he explained, when zebrafish were isolated, the hormone disappeared in the brain, but conversely when other fish were added to the tank, its expression levels rose rapidly, like mercury rising on a thermometer.

Excited by this discovery, the scientists tested if the effects of isolation could be changed by putting a previously isolated fish into a social setting.

"After just 30 minutes swimming with their kin, there was a significant recovery of the Pth2 levels," Anneser explained.

Much like human beings are sensitive to touch, zebrafish turn out to be affected by the movement of other fish, as an indicator of social proximity, the opposite of distancing.

"After 12 hours with kin the Pth2 levels were indistinguishable from those seen in socially raised animals," said Anneser, adding that this indicates a very tight link between gene expression and the environment.

Fish or flesh

Given the findings of this study, one could hypothesize that social isolation could have an impact on human brain systems that are wired to the social environment, an effect whose scope remains as yet unknown.

Perhaps studies on human subjects will find that people, too, have hormones that shut on and off based on the presence, absence, and density of human companionship, what effects these hormones have on human health, and whether long-term deprivation is dangerous or easily remedied by, for instance, lifting lockdowns.

Numerous other studies have found that the number and quality of social connections track closely with individuals' life spans, and neural research might shed light on the mechanism for this effect, and how we might be able to tackle the health effects of social deprivation sadly necessary to perhaps save our very lives.