By Humeyra Atilgan Buyukovali

ISTANBUL

One of the key things which sets Turkey apart from its European and Middle Eastern neighbors is its language.

A member of the Oghuz Turkic family and spoken by around 170 million people across Eurasia, Turkish has long been a source of national pride, with many Turks quietly pleased with their ‘difficult’, agglutinative tongue.

But the language’s proximity to other domestic and neighboring tongues has given it a rich legacy of foreign influences, from Arabic and Farsi, with later additions from French, Italian and English.

This week sees the 83rd anniversary of a local institution which has left its mark on Turkce: the Turkish Language Association.

Instituted as part of sweeping social reforms enacted in the first 10 years of the Republic, the TDK (set up in Ankara, July 12, 1932) bears the mark of the state’s founder, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

"The Turkish Nation, who could achieve protecting its country and freedom, should also protect its language from the oppression of foreign languages," said Ataturk.

This regulatory body would later become something of a control mechanism over the public's use of the language amid cultural tussles over the use of Arabic as a religious language.

The TDK started with two main aims: one was to encourage linguists and historians to research the Turkish language, and the other was to find solutions to grammatical and lexical disputes.

Professor Mehmet Kara from Suleyman Sah University in Istanbul believes that establishing TDK was "a significant step in the Turkish language."

"With such an institution, scientific work on the language became more disciplined. More language-related work appeared at the corporate level."

Citizens, however, were already dealing with a series of radical reforms on language.

The TDK’s establishment came just four years after the sudden alphabet change from Ottoman to Turkish script in 1928.

An overnight change from one writing system to another became one of the most drastic and criticized reforms of the time; many Turks had to live in a new society where they could not read even a simple letter in the new alphabet.

Implementing a Turkish-language call to prayer from the country’s mosques in 1932 was another language reform. Those who insisted on saying the prayer in Arabic could be sentenced to three months in prison, a state of affairs which lasted until the 1950s.

All such reforms on language had the aim of purging Turkish of foreign words, including those which were actively used by the public.

Turkey is not unique in this: France’s Academie francaise rails against encroaching English words in French. Iceland too has gone to major levels to keep loanwords out of its unique language.

Cultural wars in the Canadian province of Quebec – which has strict guidelines on the display and usage of French – are another example of language sensitivities.

However, times change and there is now a more relaxed attitude to the ‘purity’ of Turkish.

"It is quite normal that Turkish has borrowed many words from different cultures because Turkish is an unsettled language," says TDK president, Professor Mustafa S. Kacalin, speaking to Anadolu Agency.

"As Turks were a nomadic people, they learnt something new everywhere they went, and they added new terms to their language."

“It is our wealth; we should not be complaining about foreign words in our language," he says.

Kacalin is critical that a number of foreign words, which were a natural part of the Turkish language, were eliminated by the association in the past and replaced by invented – but Turkish – neologisms which "destroyed the diversity in the language."

What was done by the institution was "like language racism," the president says, adding that the best work by the TDK was to re-popularize Turkish-language literature.

Today, the clearest duty of the association is "to answer language-related questions of the state and the public," Kacalin says.

Like similar language watchdogs in other countries, the TDK supplies correct translations for new terms.

‘Bilgisayar,’ for instance, is a translation easily accepted by the public instead of ‘computer’.

"Another good example could be 'dolmus' [stuffed] instead of 'minibus'," Kacalin adds, referring to the hop-on-hop-off shared taxis which speed through many Turkish cities.

TDK coins and campaigns for Turkish equivalents of new loanwords. "However," Kacalin stresses, "this is not an institution which should be doing social engineering."

“All the institutions – hospitals or courts or whatever – satisfy the [public’s] needs; they do not impose the truth on people. So, it is the people who should embrace correct Turkish."

Professor Kara, an expert on Turkish language and literature, agrees:

"If the Turkish equivalents of new loanwords are not adopted by public, then the work of the scholars around the table means nothing."

During its eight-decade history, the TDK at times prioritized publishing books; in other periods it focused on information science, Kara adds.

"Today, the focus is again on publishing books," he says.

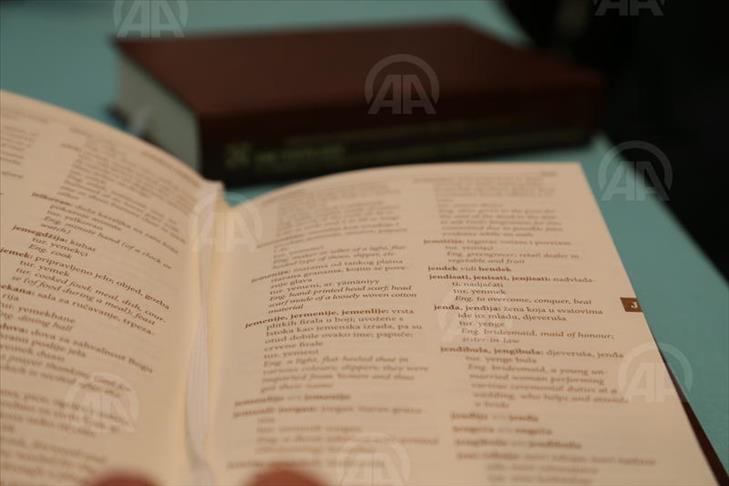

Another mission of the TDK today is to publish official Turkish dictionaries, as well as some specialized guides for glossaries or idioms, a Turkish writing guide plus linguistics books.

There are also hundreds of books and three periodicals, including the Turkish World Journal of Language and Literature, published by TDK "to reach the public and to maintain cultural heritage," says the body’s president.

Among the most significant works that the association has published until now are the Diwanu Lugat al-Turk by Mahmud Kashgari – the first comprehensive dictionary of Turkic languages – as well as Kutadgu Bilig – meaning ‘wisdom which brings happiness’ – written by Yusuf Khass Ḥajib in the 11th century.

The TDK president, appointed by the Turkish president – together with 20 permanent members – constitute the scientific board of the institution. There are around another 20 advisory experts in different fields of language studies, and over 50 employees.

The association holds periodical meetings, sometimes inviting language experts from across the world, to discuss solutions to problems of Turkish – a key aim for one of Turkey's first-established and still-functioning institutions.

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.