Comparing Turkey’s failed coup to Egypt’s successful one

Unlike Turkey’s hapless coup plotters, Egypt’s putschists spent months inciting public against country’s elected president

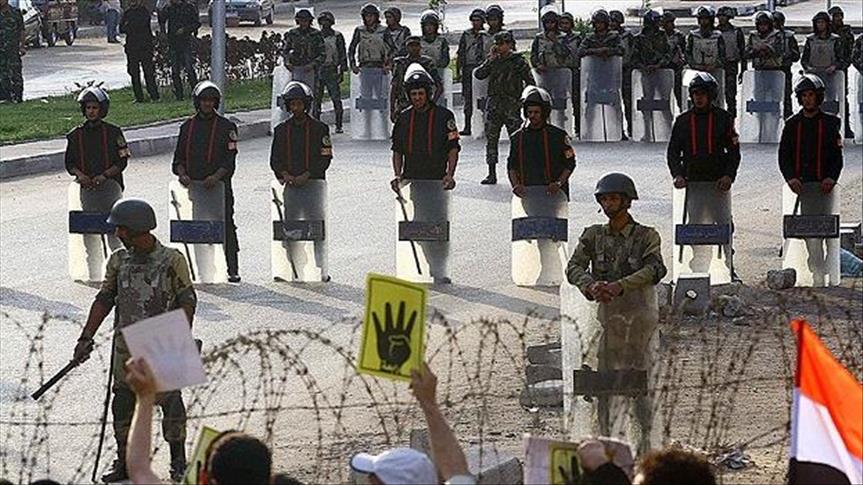

Egyptians stage rallies to protest the military coup (AA Archive)

Egyptians stage rallies to protest the military coup (AA Archive)

Egypt

By Orhan Guvel

CAIRO

On July 3, 2013, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, the then Egypt’s defense minister, announced the removal of Mohamed Morsi -- Egypt’s first freely-elected president and a Muslim Brotherhood leader -- in a move hailed by large swathes of the Egyptian public.

Almost overnight, tanks were deployed on the main streets of Cairo and army checkpoints were set up all over the country.

In the subsequent crackdown on Morsi’s supporters and members of his Muslim Brotherhood, hundreds -- maybe thousands -- were killed and tens of thousands thrown behind bars.

In the coup’s immediate aftermath, helicopter gunships fired on pro-Morsi demonstrators. Unarmed protesters, including many women and children, were cut down in their tracks by army snipers.

Many of the injured were denied treatment at hospitals and left to die on the street. Reports emerged of women being raped in police detention.

Meanwhile, the assets of known Morsi supporters -- who were now being labeled as "terrorists" by the rabidly pro-army media -- were seized.

In one of the most notorious incidents, a peaceful pro-Morsi sit-in eastern Cairo’s Rabaa al-Adawiya Square was violently dispersed by security forces, leaving hundreds -- perhaps many more -- dead.

Support

The 2013 coup that removed Egypt’s first freely elected president differed in many ways from Turkey’s unsuccessful July 15 coup bid.

For one, although Morsi won Egypt’s 2012 presidential election with some 52 percent of the vote, he only enjoyed the hard-core support of between 20 and 25 percent of the voting public, according to rough estimates.

What’s more, Morsi -- who lacked political experience (Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood had remained in opposition since its inception in 1928) -- only managed to stay in power for one year before being overthrown by the military.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, by contrast, has over 40 years of political experience and has held numerous official posts. Based on the results of the last parliamentary poll, he enjoys the support of more than 50 percent of the Turkish electorate.

As seen on the night of July 15, Erdogan managed to mobilize his supporters -- who then played a key role in thwarting the coup bid -- with a brief televised message.

Perhaps most importantly, Erdogan -- unlike Morsi -- enjoys the support of much of the country’s security, intelligence and military apparatuses.

In Egypt, by contrast, these apparatuses were still largely in the hands of elements loyal to the former regime of ex-President Hosni Mubarak.

The religious authorities in both countries, too, adopted different roles in the respective coups.

In Egypt, the Al-Azhar’s open support for al-Sisi was critical to the latter’s claim of "legitimacy", while Turkey’s religious affairs directorate (Diyanet) openly opposed the coup bid.

Mobilizing public

In the months leading up to the coup in Egypt, the Tamarod ("Rebellion") movement played a leading role inciting public opinion against Morsi and the Brotherhood.

An ostensibly "grassroots" youth movement, Tamarod spearheaded the mass anti-Morsi protests that culminated on June 30, 2013, which the army then used as a pretext to arrest the president and assume control of the country.

In addition, in the months leading up to Morsi’s ouster, Egypt’s private media ran a non-stop propaganda campaign that played a key role in inciting the public against both Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood.

In Turkey, by contrast, the July 15 coup bid took everyone by surprise. The coup plotters did not pave the way for their venture by trying to rally the support of the public or their potential opponents elsewhere in the military establishment.

From the outset, the July 15 coup attempt -- with a few notable exceptions -- met opposition from the Turkish public and Turkey’s key security institutions.

In Egypt, Morsi and his administration largely failed to counteract the private media’s round-the-clock propaganda attacks, which prepared public opinion for the army’s successful coup bid.

With the exception of a handful of news websites, the Egyptian media overwhelmingly supported the coup, while international media coverage remained neutral or -- in some cases -- even supported the coup.

Except for Turkey’s Anadolu Agency and Qatar-based broadcaster Al-Jazeera, no international news agencies adopted a negative stance vis-à-vis Egypt’s coup or portrayed it as a setback for democracy.

By contrast, almost all Turkish media outlets -- including those controlled by the political opposition -- came out firmly against the putsch attempt, with most broadcasting the president’s calls to the public to hit the streets in opposition to the coup.

Notably, in the early hours of July 16, the Egyptian media -- prematurely as it turned out -- celebrated the "successful coup" in Turkey.

The Sky News Arabia television channel (based in the UAE, a staunch supporter of Egypt’s army-backed regime) misreported at one point that President Erdogan’s plane was en route to Germany after failing to land in Istanbul.

In Egypt, hundreds of thousands -- some say millions -- took to the streets to support the army’s seizure of power from the country’s first democratically-elected president, thereby ensuring the coup’s success.

In Turkey, by contrast, citizens hit the streets to oppose the coup and express their support for the president and the country’s elected government.

International reactions and states of emergency

Except for Turkey and Qatar, important countries and institutions -- including the UN, the EU, the U.S. and the West in general -- accepted Egypt’s coup as a fait accompli.

In the wake of the putsch, as Morsi’s supporters were being gunned down and incarcerated, al-Sisi received hefty financial support from the Gulf States to prop up Egypt’s moribund economy.

Following his successful coup, al-Sisi imposed a state of emergency that was used to arrest Morsi administration officials and Muslim Brotherhood members and confiscate their property.

Unlike the case in Egypt, the state of emergency declared in the aftermath of Turkey’s failed coup bid has not entailed any restrictions on citizens' basic rights and freedoms.

Rather, it is aimed entirely at expediting the purge of coup supporters from Turkey’s most vital institutions of state.

Turkey’s July 15 coup attempt is believed to have been orchestrated by followers of U.S.-based preacher Fetullah Gulen.

Gulen’s followers are accused of trying to infiltrate Turkish state institutions -- especially the military, police apparatus and judiciary -- with the aim of creating a parallel state.

At least 246 people, including civilians and security personnel, were martyred -- and more than 2,100 injured -- during the illegal July 15 putsch attempt.

*Orhan Guvel served as a representative of Anadolu Agency’s Middle East bureau in Cairo in the wake of Egypt’s 2013 army coup

Anadolu Agency website contains only a portion of the news stories offered to subscribers in the AA News Broadcasting System (HAS), and in summarized form. Please contact us for subscription options.